Richard Dunn: Some Decades, essay by Keith Broadfoot (download Pdf with images)

RICHARD DUNN: SOME DECADES

Keith Broadfoot

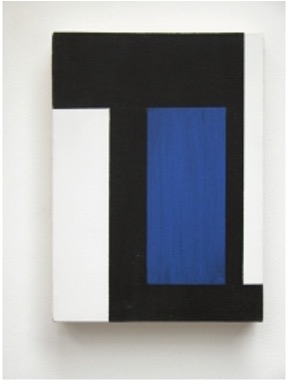

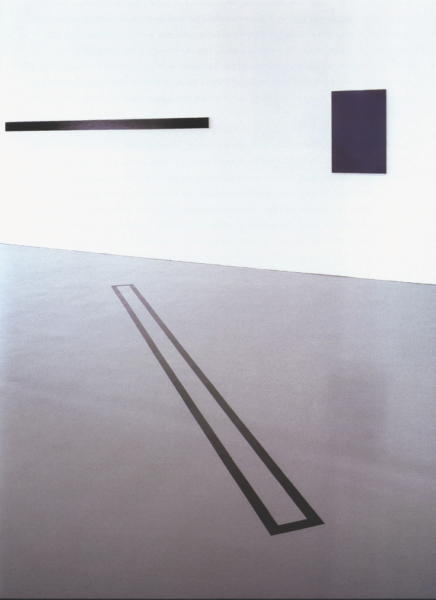

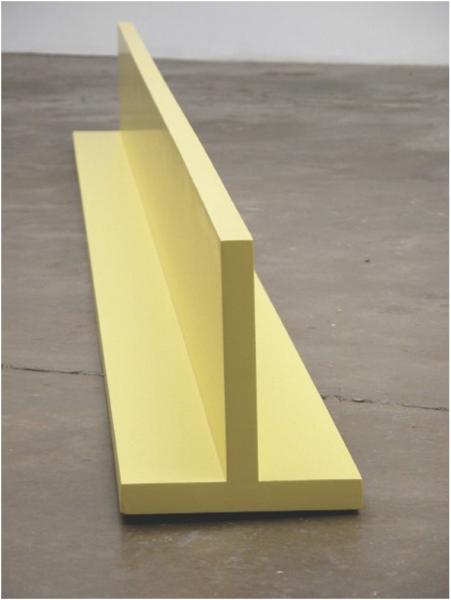

Here is a fragment of the work from different decades: a floor piece from the late sixties, a large wall piece from the late seventies, a small painting from the mid-eighties and a painting from 2011. In a larger space it could have been a piece from each of the last six decades giving this exhibition a certain logic. However that would be a false ordering of things that have been compelled into existence, in a way without more logic than that which asks “what if this is done?”

So here is a dialogue of periods; ideas that continue, or are transmuted, that move back and forth disregarding time. In this sense there is no time, only actions – and things that can speak to each other and to us in a space. This collection of objects is only one of many possibilities that could have been assembled to function in this kind of way, where each potential variation would make a new dialogue with, and for us.

Decades Past and Present

In Some Decades there are four works from four different decades. The earliest work is a 1969 floor piece and the latest a small painting from 2011. However as Richard Dunn suggests in his introductory remarks to the exhibition, it is hoped that these works will not simply be approached in terms of a chronological order, as if we were viewing them in terms of a standard retrospective which would arrange the works with the intention of highlighting a linear form of development and progression. The artist rather speaks of a desire for dialogue, a form of relation that does not necessarily place a sequential priority of one work over the other. In dialogue one work is not to be read as the terminating conclusion to another. Equally one work is not to be positioned, conditioned perhaps by the underlying biographical path of the artist, as the ‘mature’ or ‘resolved’ form of what precedes it. It is rather as if we are to imagine that the works exist in a state of potential equality, together in the same present or perhaps at different points along the same extendable plane. Why is this? How are we to approach the works in this manner? In response to the exhibition let me briefly offer some possible suggestions.

Noel Hutchison has argued that from the mid-1950s up to the time of the appearance of works like Dunn’s 1969 Floor piece, Australian sculpture was dominated by a style that he labelled ‘residual organicism’. The common element across a broad range of sculpture was, as Hutchison perceived it, a ‘distinctive concern with organic growth—be it in either form or principle, in either mutation or creation.’1 Thus, without actually being representational, the sculptures developed organic associations, giving the appearance of being plant-like, rock-like or animal-like. Such an organic approach can be understood as a response to modernist sculpture’s removal of the pedestal. The organic arises as an overcompensating for this loss, for the very loss, paradoxically, of any sense of an organic grounding. Without the base on which a representational figure would stand, what form, what arrangement, what constructional order, should a sculpture adopt? The organic conception of a sculpture could provide an answer and, more importantly, a much-needed sense of certainty, giving to a sculpture’s formal conception the sense of an inner necessity.

In her book on the history of twentieth-century sculpture, Passages in Modern Sculpture, Rosalind Krauss offers a crucial insight into the reason for the emergence of the organic approach. Once sculpture’s ambition towards realistic representation is discarded, she suggests, ‘the possibility arose—as it had not for naturalistic sculpture— that the sculpted object might be seen as nothing but inert material.’2 How abstract sculpture overcame this potential problem was by the suggestion of an analogy between the way that it took shape and the logic of organic growth. Krauss observes how the principle of an abstract sculpture’s formal development was dictated by the symbolic importance given to a central interior space from which it was imagined a life-giving energy force radiated. The key point of focus in an abstract sculpture, therefore, was its centre: from an interior energy source, Krauss writes, a sculpture’s ‘organisation develops as do the concentric rings that annually build outward from the tree trunk’s core’.3 From this example of how an organic metaphor is utilised, what Krauss specifies as important in the organic conception of sculpture in the work of someone like Henry Moore or Jean Arp, is not so much how you may notice their tendency to use organic materials such as eroded stone or rough-hewn wooden block, but instead how the illusion is created of there being ‘at the center of this inert matter…a source of energy which shaped it and gave it life’.4

With the sense that the sculpture evolves from the centre there is a displacement of attention away from the function and presence of the pedestal. It is as if the fact that the essence to a sculpture is to be found within its hidden interior is a way of negating how sculpture defines itself in relation to the pedestal. The important result of this sense of growth from the interior is that the contextual placement of the sculpture—its site—is not a determining factor in the production of meaning. In fact, by taking everything away from the sculpture’s environmental placement and locating the key to the sculpture’s essence at its centre, sculptors believed that they were set on a quest to give form to universal truths. Think, for example, of how Henry Moore was representing the mother and child as a universal condition: it was not this particular mother and child but a couple that was abstracted to stand for a kind of shared humanity. Also, when sculpture began to become more explicitly abstract and promote itself as organic, think of how the organic can evoke the supposedly eternal and timeless qualities of nature, suggesting that inside sculpture there is to be found a truth of nature that is beyond any specific cultural context.

Considering this, one can appreciate that the arrival of minimalism may have initially seemed like a dramatic shift. There is a seemingly all-encompassing change from nature to culture. Using readymade, industrially produced materials, minimalism does not attempt to use material in an illusionistic manner, in the sense that there would be the suggestion that the resulting sculpture was crafted in response to any inner-life radiating from within. When a minimalist artist such as Carl Andre forms an artwork out of a line of commercially produced fire-bricks, the fire-bricks obstinately remain fire-bricks—the bricks are simply there and one does not search for their meaning or reason for being in any veiled central core. With this kind of sculpture, therefore, everything remains on the surface, with no compositional key to be sought from any interior space.

To use the example of Andre again, a sculpture consisting of a series of identical fire-bricks placed in a line lacks any idea of a compositional centre, with the repetition of similar elements eliminating the sense of there being any hierarchical relationships within the work. No emphasis is given to one part over any other part. Furthermore, with this lack of composition, any ending to the repetition of the similar units can only seem to be arbitrary. Why should the length of the line of bricks be 10 metres or 100 metres? Is it simply as long as the gallery space permits? From the organic to the geometric, the change is therefore not only from centre to surface, because without a centre what results is that there is no internal logic which would set a limit to a sculpture’s extension.

This gives us a starting point to approaching Dunn’s 1969 Untitled Floor Piece. Yet, as always, it is the specific differences that lead to a better appreciation. And indeed the dialogue established with the other works creates the possibility for developing this awareness. Each of the works deal with the lack of a centre in related though also different ways. In the paintings – though immediately you need to add that the floor piece is also a painting – you have the sense of an ‘off-centre’ framing, though ‘off-centre’ in relation to what of course you cannot say, as you are also aware that there is no longer any locatable centre. This characteristic could initially be thought within the self-reflexivity of a high modernist context. With each of the works, in the absence of an interior, it is as if the frame to the work has become the work. Thus in the 2011 painting Untitled for example, the ‘framing edge’ to the canvas is proportionally increased (or decreased depending on the direction) as you move around the painting, with such a circular movement deflecting the absence of any centre.

With Untitled Floor Piece as well it could be understood to be the presentation of the frame itself or, what is the equivalent in sculpture, the pedestal. It is the reduction of the pedestal to a kind of elemental abstract form. There is the flat plane of the horizontal base and at right angles to this the vertical figure. Though equally of course you could say that there is no longer the possibility of drawing a distinction between the two, of definitively naming one or the other. The titling of the work as a ‘floor’ piece indeed highlights the removal of the mediating element of the pedestal. It is perhaps then that the extension of the work is there to fill in for the absent interior of the work. An idea reinforced by looking at another floor piece from 1969, Line, which consists of two-inch masking tape taped to the floor in a rectangular shape. Here it is as if the tape is marking out the work that is not there, creating a hole, a gap, only presenting the indicating sign of a work vacated of any sense of an interior.

All this however is to remain within the paradoxes created by the self-referential ambitions of modernist painting. Although much of this is useful to situate Dunn’s work, it is also limiting. To move elsewhere let us consider a slightly earlier work. In Terence Maloon’s catalogue essay to the AGNSW’s ‘retrospective’ of Dunn’s work from 1964 to 1992, he pinpoints one work, his 1968 painting Untitled (New York City) #1, as decisive in marking the singular trajectory of his art. As Maloon relates the context to this painting, this was a work that Dunn completed after visiting New York that year and in particular seeing Barnett Newman’s painting, Vir Heroicus Sublimis, at the Museum of Modern Art. Untitled (New York City) #1 is approximately two metres high and five metres wide, consisting, as Maloon describes it, ‘of five horizontal bands of chrome yellow household enamel paint alternating with six thinner bands of black acrylic paint, and the parallel bands extend over two abutted canvas panels.’ However immediately following the seemingly self-evident nature of this plain description, Maloon astutely draws our attention to a number of unanswerable questions:

‘Are there five or six horizontal divisions? Does the juncture between the two canvases imply their fusion or fission? Is the surface governed by continuity, repetition or rupture? If we focus on the yellow and black bands, which set of bands is “figure” and which “field”?’ This proliferation of undecidable characteristics leads Maloon to the assessment of the singular significance of this painting to what he calls ‘Dunn’s development’, for it ‘indicates how well he understood the way that Newman’s abstract paintings lend themselves to dialectical performance and self-engendered paradox. This is a feature that Dunn made his own in “Untitled (NYC)”, and it has been his ever since.’5

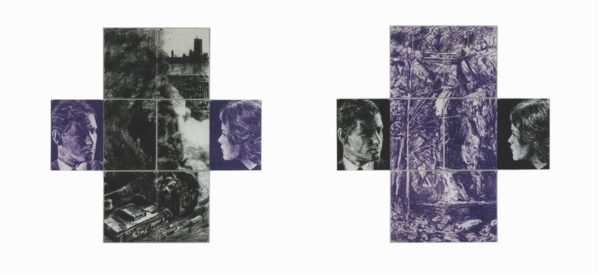

Maloon’s isolating of this work as the key turning point in ‘Dunn’s development’ is wonderfully suggestive and perceptive. Maloon moves forward through different decades of Dunn’s work, following this ‘dialectical’ performance’ and ‘self-engendered paradox’, and giving particular emphasis to how in 1985 ‘Dunn settled upon a format which embodied the principles of crossing, intersection and abutment.’ From this Maloon makes a final and equally suggestive theoretical step, linking this format, which Maloon terms a ‘cruciform’ or ‘crossed’ format, with structuralism, in particular with Jacques Lacan’s diagram for the crossing of metaphor (in the vertical) and metonymy (in the horizontal). Referencing two drawings from 1985, Untitled (Couple and Fire) and Untitled (Couple and Waterfall), Maloon suggests that a remarkable parallel (or maybe it is also a crossing) occurs: ‘The exact (but completely accidental) concordance of Dunn’s image and Lacan’s theory indicates how closely Dunn’s poetics correspond to Structuralism.’6 I will here follow Maloon’s lead, pursuing a little further the theoretical connections he suggests.

In returning to Untitled (New York City), although Maloon highlights the Newman influence, undoubtedly following the artist’s own recollection on what took place, the connection with Newman is not an immediate one. If Newman’s ‘signature’ is the vertical ‘zip’, the stretched horizontal bands in this painting would seem a strange divergence. With the horizontality and also with the kind of high-keyed colour effect, what Maloon describes as a yellow ‘at optimal brilliance, at saturation-point’, it is perhaps more Kenneth Noland than Newman. Yet, in the end, I think the Newman is still right, and this because it is the unexpected way in which the connection with Newman is established that dramatically adds to the decisive importance that Maloon gives to this work. The verticality in the painting, in effect Newman’s ‘zip’, has become not a line ‘in’ the painting, part of the painting, but a split, a gap. But to say it this way is not exactly right as the use of quotations marks already indicates (and it is remarkable, as we will see, that everything about the painting would in some way need to be placed in quotation marks). To build on the paradoxes that Maloon identified, it is in fact a line at once ‘in’ the painting but then equally not. Created from an absence, a between space, it can at one and the same time join and divide, create one painting at the same time as it produces separate parts, indeed create not a painting but paintings in the plural. It is, impossibly so, a continuity and a discontinuity. In all of these qualities, the line in this work is the same as it is in the 1969 work Line, or equally, it is this line which constitutes the Untitled Floor Piece of the same year. This also because even the vertical nature of the line in Untitled (New York City) should be placed in quotation marks, as the painting can also be understood as marking the shift to what Leo Steinberg famously termed the ‘flatbed picture plane’, using this term to capture a loss of distinction between the vertical and horizontal. With Untitled (New York City) there is the verticality of it as a painting placed on the wall, but that does not fully prevent the perception arising that the ‘vertical’ line we see can be read as a horizontal line, as if we are looking down at the work from a position above. With this shift – or maybe it is an oscillation – between the vertical and the horizontal, the identity of painting can indeed also begin to shift. This painting can be a sculptural object – Maloon says that it ‘is stunningly real. It is an independently existing object’ – as Untitled Floor Piece can also be a sculpture which is at the same time a painting.

To however once again attempt to bring to a halt the proliferation of ‘self-engendered paradox’, why, more fundamentally, Newman? Why does Newman’s ‘zip’ become this ‘abutment’, this ‘crossing’, this ‘gap’? It is, I think, a question of scale. Newman searched in his lines to present something like the origin of scale, or even perhaps more simply, measure. Throughout Dunn’s work, a common element is a heightened concern with matters of scale and measure, or variations of the same such as proportion and relation.

Now it is of course quite common for an artist interested in abstraction to develop a fascination for all things mathematical. One way of understanding the reason for this is that the mathematical is functioning in the same way as what I previously outlined with the organic. If a painting is structured according to some mathematical progression or series, then it is as if, as with the idea of an organic growth, it is proceeding by itself. The work, without in some ways even requiring the intervention of the artist’s hand, can seemingly auto-generate its own internal logic, giving to the inert abstract matter a reason for being, a principle to establish its autonomy. Yet, if this is the case with many abstract artists it does not encompass Dunn’s approach. And here Maloon’s selecting of Dunn’s Untitled (New York City) as the decisive work is telling, because what this work evidences and what subsequently follows from this work, is that it is equally where the mathematical relation falters, that is the gaps and ‘crossings’ that create disturbances and antagonism, that are of equal concern. No measure, no proportion, as if the artist is saying, without at the same time discord, opposition and contradiction. Why is this? How can we understand this relation in Dunn’s work?

Consider the work Growth Plan for Meno in this exhibition. The title is referencing an exchange between Meno and Socrates from Plato’s Dialogues. Under discussion is the doctrine of knowledge as recollection, the proposal that all knowledge is somehow present in our souls at birth, simply requiring our recollection to activate. Socrates is going to prove this is so to Meno by showing how he can take anyone, in this case a lowly slave, and through a process of questioning demonstrate how the slave can recollect knowledge that he thought he had no knowledge of. The central scenario involves Socrates first drawing out a 2 by 2 square in the sand and asking the slave to produce a square twice as large in area. The slave immediately responds by making a mistake, thinking that doubling the square’s side will double the area. In the sand Socrates shows to the slave how this produces a square not double in area but quadruple, 16 instead of 8. In order to let the slave find the required solution Socrates cuts off the corners of the larger square, thus halving its size, and producing a square double the original size. (The following 3 diagrams represent the different steps.)

As it so happens, and this adds to the ‘exact (but completely accidental) concordance’ which Maloon discovered, this dialogue, and crucially what is traced in the sand, was central to the ideas of Lacan. From Socrates procedure Lacan finds a key demonstration of his idea of the emergence of the symbolic. After outlining what takes place in the dialogue Lacan provides the following commentary:

Don’t you see there is a fault-line between the intuitive element and the symbolic element? One reaches the solution using our idea of numbers, that 8 is half of 16. What one obtains isn’t 8 square-units. At the centre we have 4 surface units, and one irrational element, √2, which isn’t given by intuition. Here, then, there is a shift from the plane of the intuitive bond to a plane of symbolic bond.7

Socrates’ trick, what is not fully revealed, is that he finds a relationship between things that are incommensurable. Replacing squares with triangles, the relationship is not the same as that of whole numbers to each other, that is to say twice 2 is 4, but of the relationship of the side of the original square to its diagonal, 2 to the square root of 2, two elements that are without common measure. Lacan further explains the significance of this:

This demonstration, which is an example of the shift from the imaginary to the symbolic, is quite evidently accomplished by the master. It is Socrates who effects the realisation that 8 is half of 16. The slave, with all his reminiscence and his intelligent intuition, sees the right form, so to speak, from the moment it is pointed out to him. But here we put our finger on the cleavage between the imaginary, or intuitive, plane – where reminiscence does indeed operate, that is to say the type, the eternal form, what can be called a priori intuitions – and the symbolic function which isn’t at all homogenous with it, and whose introduction into reality constitutes a forcing.8

My argument is that what I have been referring to as the line in Dunn’s work is this ‘forcing’, or from the previous Lacan quote, this ‘fault-line’. Although in this instance it may just be the gentle tracing of a line in the sand, Lacan is emphasising its force, the fact that the symbolic only emerges because of an original violence.9 Also Lacan is stressing that the symbolic is something that cannot be recalled or remembered, it is rather that which breaks and disrupts memory. The symbolic element, like the irrational element √2, does not emerge gradually, step-by-step, its origin is always lost, it is just with the lightening sketch of a line that it is there. Yet at this instant all changes, the past is rewritten, and it is as though this symbolic element has always been there, its placement seemingly right and indisputable. The line in Newman is this symbolic stroke, the force of what Newman often referred to simply as the ‘law’. It is then, I also wish to suggest, the temporality associated with this symbolic forcing that accounts for the particular relationship between the works in this exhibition at Factory 49.

To conclude, I might then just slightly rephrase Richard Dunn’s introductory remarks about the exhibition when he suggests that in a sense ‘there is no time, only actions – and things that can speak to each other and us in a space.’

Within the dividing line of the present, what Dunn is exploring are actions that take place in no time, that place and time in which anything that is fundamentally new arises.

Keith Broadfoot

Department of Art History & Film Studies

University of Sydney

_____

1 N. Hutchison, ‘Australian Sculpture in the 1960’s: Part 1’, Other Voices, Vol. 1, No. 3, October/December, 1970, p. 11.

2 R. Krauss, Passages in Modern Sculpture, Cambridge/London: MIT Press, 1981, p. 253.

3 Krauss, Passages in Modern Sculpture, p. 253.

4 Krauss, Passages in Modern Sculpture, p. 253.

5 Terence Maloon, ‘The Dialectical Image’, in Richard Dunn The Dialectical Image – Selected Work 1964 – 1992, Sydney: AGNSW, 1992, p. 12.

6 Maloon, ‘The Dialectical Image’, p. 30

7 Jacques Lacan, The Seminar of Jacques Lacan Book II. The Ego in Freud’s Theory and in the Technique of Psychoanalysis 1954-1955, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988, p. 18

8 Lacan, The Seminar Of Jacques Lacan Book II, p. 18

9 For more on the relation between violence, √2, dialogue and the diagonal, see the chapters on the origin of geometry in Michel SerresHermes. Literature, Science, Philosophy, Baltimore & London: The John Hopkins University Press, 1982

SOME DECADES

(An exhibition at Factory 49, Sydney, November 2011) 49 Shepherd St, Marrickville, Sydney, factory49.blogspot.com